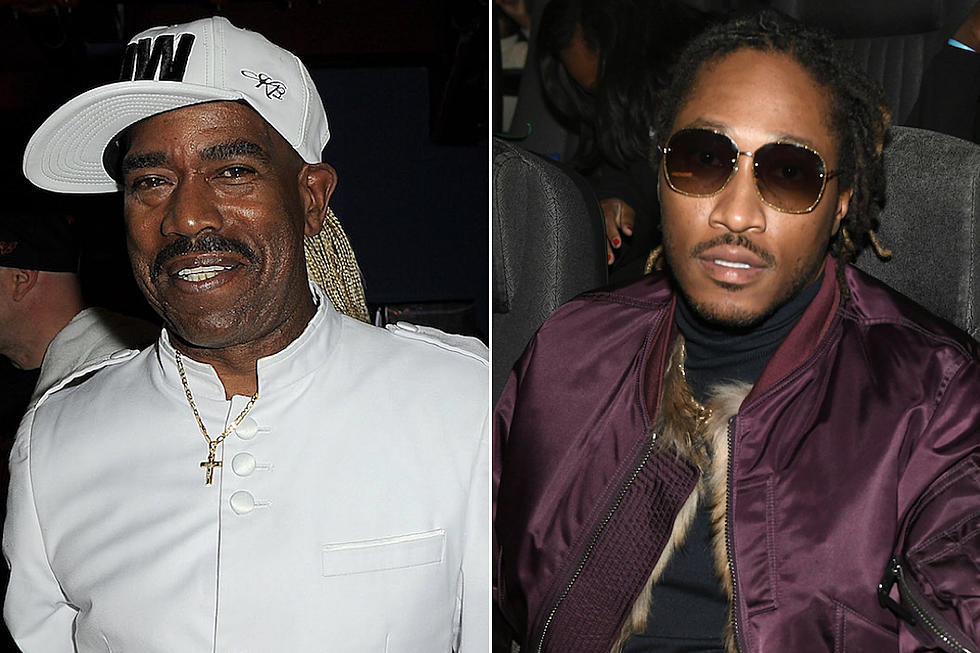

David Banner On Lecturing, Hip-Hop Sites and Irving Plaza: ‘Our Pain Is the World’s Entertainment’

David Banner doesn’t mince words. Over the past 15 years, the Mississippi-raised rapper, producer, director and entrepreneur has become as well-known for his candor regarding social and political issues as he is for hits like “Like A Pimp” and “Cadillac On 22s.” He’s been behind the boards for some of the most iconic rap tracks of the 2000s and he’s developed a formidable media company with A Banner Vision, but David Banner is as restless and ambitious today as he was as a young artist those years ago. And Banner is adamant that his latest creative inspiration, showcased on his forthcoming album The God Box, give voice to a spirit in music that he believes is lacking right now.

We talked about that spirit and whether or not he can connect the hip-hop that inspired him to become an artist to the hip-hop that moves the crowds today.

“I can only speak on what I was raised thinking hip-hop was about,” Banner says, a certain resignation in his voice. “I watched my culture because I am a part of it and…you know, it’s sorta like religion; I think for a while, people gave us these rules in hip-hop so they can control it; not because these were true rules to live and abide by. But I look at hip-hop--and hip-hop is one of the few things that you can get paid to do when you don’t have to know how to do nothing inside of it. As a matter of fact, many people brag about not being a rapper. How you gonna brag about not being a rapper but you’re rapping? And don’t rap! Then get out of the culture.

“People are proud to not know how to do—it’s like it’s cool to be dumb. It’s cool to kill your own. I’m not criticizing anybody. I’m just bringing to light what we say and what we do. We make hip-hop so easy that it’s not an art anymore. If anybody can do it—why purchase it? My little brother can do it.”

The God Box is due later this summer, but Banner has already dropped the politically-charged "Black Fist" with Tito Lopez, the ballad “Marry Me” with Rudy Currence and the explosive “My Uzi” with Big K.R.I.T. It’s the latter song that Banner says is a clear indication of his intention for his new album.

“When I dropped ‘My Uzi,’ that was my thesis statement to hip-hop,” he says. “I don’t think there was too many songs that were released this year that were on that level. And I think that’s a representation of The God Box. People talk about verses, me and Big K.R.I.T., line for line and verse for verse, you can’t find no flaw in that song. Beat-wise, I put a fucking symphony orchestra at the end. That wasn’t no sample. John Debney--who scored The Passion of the Christ, Iron Man 1, 2 and 3--did an original. That wasn’t something he pulled out—he did an original composition for me for the end of ‘My Uzi’ because I wanted to show people quality in hip-hop. We don’t need to sample—since y'all want to create these crazy sample laws. I’ll create my own.”

Creating your own is a recurring theme in our conversation. Banner passionately derides the lack of ownership in so many black spaces—from hip-hop itself to hip-hop commentary. He makes it plain that he has an issue with most hip-hop sites.

“I’m so sick of hip-hop blog sites that don’t report on the man that just got hung in Ohio,” Banner says. “They don’t report on the cop being released in the Freddie Gray case. It’s like hip-hop blog sites and things that are supposed to be hip-hop--they’re getting worse than FOX News.”

In particular, Banner took exception to how the T.I. concert shooting at Irving Plaza in New York City was covered and the reaction to it.

“A lot of these times at these rap concerts—they aren’t violent like that anymore,” he says. “You get one incident out of 20 concerts and you want to make it the poster child for what happens at rap concerts. [T.I.] tours all over the fucking world and one thing happened—so what? These white kids be shooting and fighting and at Ole Miss they burned down half the town! After a football game! These white folks go crazy and we say nothing—black folks don’t even criticize them. I know white media isn’t going to do it because they respect their culture and their kids and they’re going to protect them. That’s why white people don’t put white kids in the news—because they’re protecting their children. We have bought into commercialism and we sell our kids because we sold our soul. What won’t you report? And most of these blog sites are owned by white people anyway. With black fucking faces [out front.] How dare you say you’re hip-hop but add nothing to the fucking culture.

“When our stars do something; for four or five days, [you see] it on TV. The descendants of Africans or Africans, in general—our pain is the world’s entertainment. So I won’t even waste my time on that bullshit, bro. C’mon, my dude. We want that drama. As consumers, that’s what we want to do.”

In the wake of the shooting, which occurred in a green room backstage while T.I. was set to perform and unaware what was happening, the hip-hop star has lost a Florida booking and several New York rap shows have been canceled by Live Nation.

“It’s sad and hard enough to have rap concerts anyway because they ran the insurance up because of stereotypes,” Banner explains. “We almost have to have a million dollar insurance policy just to throw a rap concert in the first place. They don’t want black folks to do nothing but go to jail and work for them. And I’m tired of it and won’t nobody say nothin’ about it. We let these blog sites and these people who are not in our community paint us. They don’t even add nothing positive. When you go on these talk shows, they won’t play your music; but they want to know about everything negative in your life. They’re not even smart enough to build your brand up so that they can tear it down! Just leeching.

“Because I make the type of money that I make, I can talk a little shit. I’m just tired, bro. Because I’m meditative and a man of peace, I try not to say nothing and I try not to hoop and holler. But I’m tired, bro. You’ve got all these people behind these computer screens but our children are dying in real life.”

At 42, Banner is an elder in hip-hop circles and he takes that position seriously. He’s gotten some criticism on social media for his tweets regarding women and respectability and he’s also been criticized for earlier songs like “Play” that were blasted as degrading or objectifying. If anything, Banner has constantly challenged himself to evolve; and part of the reason is that he wants to be an example.

“Let me tell you something that Ludacris’ manager Chaka Zulu told me. He said ‘David Banner, how do you judge men through the ages? By the art.’ When you look at Egypt what do you look at? The walls! He explained that our generation is going to be [defined] by our art. So they’re pushing our art and making us look like heathens from an art perspective. So when they pull out these tanks and blow us away, historically it’ll be justified by our art. They’ll say that we are savages. And I was like ‘Whoa!’ I have to leave a thesis statement for black men. That is my fucking responsibility.”

He dismisses the idea that the codeine and party raps of 2016 are simply the result of a younger generation speaking to and for itself.

“It’s not a generational shift, that’s some slave shit,” Banner scoffs. “Grown folks rapping the same way these kids are rapping. If there is a generation gap, its because we allowed the gap to be there. We were not there for those children. It’s not the children’s fault—it’s our responsibility to connect with them. We walked off and turned our nose up the same way our parents did.

“When I was in Ferguson, them children on the street; that was kids from 15-27, for the most part. And they kept asking me ‘Banner, where are our parents?’ For the most part, me and Dasari X and a couple more men were the only grown folks out there. For the most part. David Banner, Talib [Kweli]—I don’t know if you’d consider [J. Cole] a elder, but for a lot of them kids and the age that they were—he is an elder. It’s the same way in rap. So you can’t blame these kids—that’s our responsibility to be there. Regardless of whether I’m making a whole lot of money [or not], it’s still my responsibility to be an example of how a man is supposed to be in hip-hop.”

However anyone may feel about his perspective, Banner's commitment and passion are both evident in the way that he talks about his community and his art. He wants to reach people; and he's eager to "shine a light."

"I went through my Twitter feed today and I just watched everything that we were concentrating on and I started listening to the music," he shares. "And I was like 'these folks are doing some of the most treacherous things in the world and we have no fucking idea.'

"I’ve started lecturing all over the world—the God Box Lecture Series," explains Banner. "Anywhere from 500 to 1200 people. In three years, I’m going to be lecturing in front of 5,000 people—watch my word. My lectures are becoming like concerts—people wrapped around the corner."

And Banner makes sure to emphasize that he is not anti-youth. No matter what criticisms he and others may share, he isn't blind to the fact that some of today's biggest artists are showcasing a socio-political awareness on highly-visible platforms.

"I think this generation is actually the best generation," he says. "They don’t give a fuck about religion. They don’t give a fuck about these leaders. And for everything negative that we have to say; look who’s selling the most: J. Cole. Kendrick Lamar. I haven’t been to a Big K.R.I.T. concert that wasn’t sold out. People wanna hear it. But we expect the system to show us that. That’s idiotic. It’s stupid. It’s stupid to expect our oppressor to give us the right information that would set us free. They want us to be niggers. They want us to kill ourselves. They want us to be dumb so we won't do nothing but entertain them."

And Banner refuses to be someone who is just here to entertain. As he pushes himself, as he shares his perspective with the media, with fans, with those who attend his lectures; it's all informed by a sense of purpose. He knows who he is. Most importantly, he knows who he is not.

"Regardless of who your favorite rapper is, they’re still a jester," Banner declares directly. "All of us. We’re all up here to sing and bounce around for somebody who’s richer than us and their entertainment, at the end of the day. When I realized that, that’s when I started doing other things. If I’m going to entertain, then I’m going to entertain the way I want to entertain."

And he wants all artists and those who support artists to be mindful of who the gatekeepers are that present these icons to the people. Ownership. Control. Those things are never far from his mind.

"Think about our people as a whole and what quantifies being a star in their eyes. We have to usually get a record deal. We usually have to be in their movies. So in order for us to lead our people, we almost have to sell out. Because we don’t see any value in ourselves. Think about my first album—I was going to put that same album out on the streets. If I would’ve sold that shit on the streets and I wouldn’t have gotten signed by Universal, people would’ve still thought I was just that crazy nigga from Mississippi with an independent album. What made that album dope in the eyes of my people was when New York put that stamp on it and sent it back to my people. So that means white folks have to tell our people who their leaders are; and they’re not going to elect somebody that’s really gonna change shit. So it’s a conundrum. Until we have the internal fortitude to love and do for ourselves, shit ain’t gonna change. Because your favorite rapper ain’t coming back to save you. Jesus ain’t coming back. Obama ain’t gonna help you.

It’s going to come from the people.”

You can pre-order David Banner's The God Box HERE.

Check out "Black Fist" in the video below:

More From TheBoombox

![David Banner: ‘White Folks Got Black Folks So Petrified They Tell You How to Protest’ [VIDEO]](http://townsquare.media/site/625/files/2016/07/David-Banner-Bennett-Raglin.jpg?w=980&q=75)

![David Banner Finally Drops ‘The God Box’ [LISTEN]](http://townsquare.media/site/625/files/2017/05/david-banner-god-box.jpeg?w=980&q=75)

![David Banner Drops ‘Magnolia’ with CeeLo Green and Raheem DeVaughn Ahead of ‘The God Box’ LP [LISTEN]](http://townsquare.media/site/625/files/2017/05/David-Banner-Magnolia-The-God-Box.png?w=980&q=75)

![David Banner: ‘It’s Not White People’s Racism That’s the Problem, It’s Black People’s Lack of Racism’ [VIDEO]](http://townsquare.media/site/625/files/2017/04/David-Banner-on-The-Breakfast-Club.jpg?w=980&q=75)