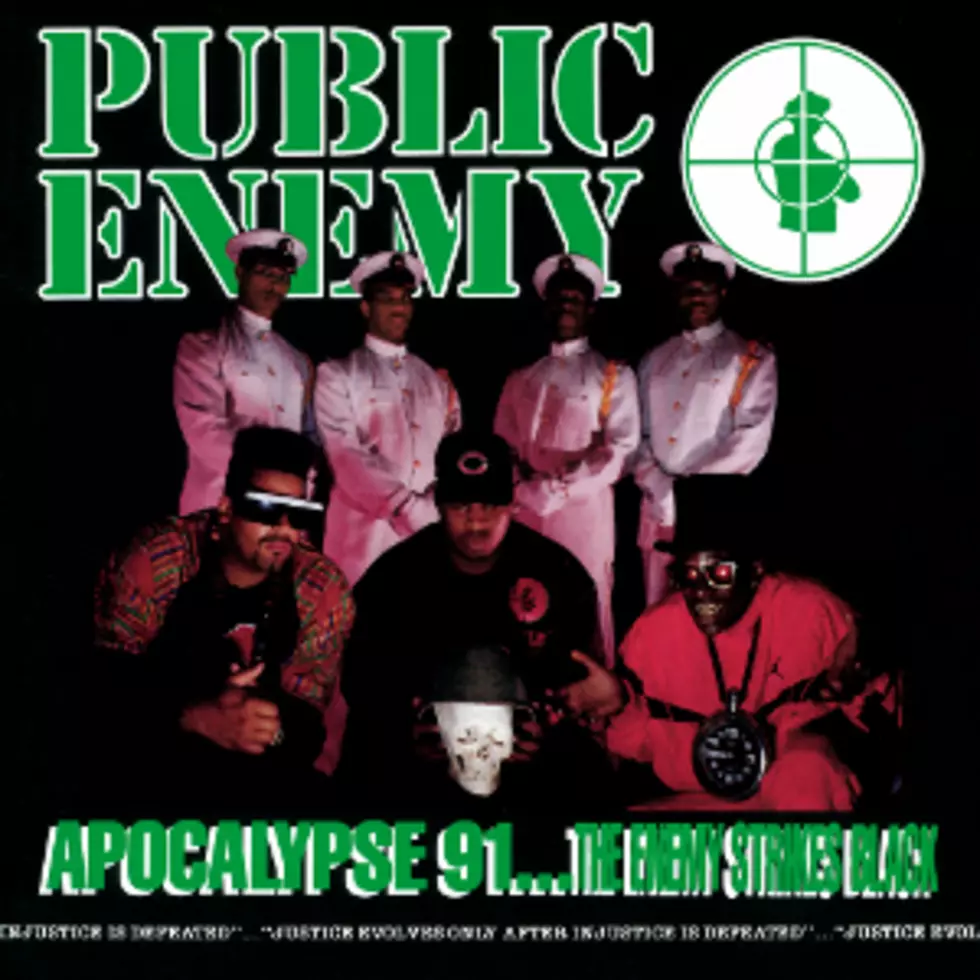

‘Apocalypse 91…The Enemy Strikes Black:’ Public Enemy’s Urgent Fourth Album Is as Timely as Ever

Public Enemy had ended the 1980s at the pinnacle of their power, with "Fight the Power" becoming a hip-hop anthem in the summer of 1989 as the sonic backdrop for Spike Lee's classic Do the Right Thing. And P.E. had followed that high-profile success with their critically-acclaimed third album, 1990s Fear of A Black Planet; a fiery masterpiece that saw the Bomb Squad at the height of their sonic assault and Chuck D's razor-sharp commentary focused on everything from 1989s Virginia Beach Greekfest incident ("Brothers Gonna Work It Out") to Hollywood stereotyping a la films like Driving Miss Daisy ("Burn Hollywood Burn"); with Flav's "911 Is a Joke" playfully (but shrewdly) skewering the systemic failures of public services to the Black community.

N.W.A. may have been hip-hop's most notorious act circa 1990/91, but Public Enemy was still the most influential, a mantle they'd assumed from Run-D.M.C. after 1988s It Takes A Nation of Millions To Hold Us Back made them critical darlings and unlikely crossover stars. And the political climate of the early 90s only served to fuel the group's artistry. In a year that saw no shortage of classic albums from Gang Starr, Ice Cube and A Tribe Called Quest, Public Enemy followed their biggest album to date with a scorching response to tabloid attention, mainstream radio, corporate exploitation and race relations in the time of Rodney King.

But by 1991, Chuck D's status as hip-hop's most potent voice wasn't as unassailable as it had been in 1989. In the year and a half since the release of ...Black Planet, Ice Cube had emerged as a dominant figure in hip-hop. He'd been featured on that album's "Burn Hollywood Burn," and the Bomb Squad produced most of his 1990 debut AmeriKKKa's Most Wanted, which also featured both Chuck and Flavor Flav. In stepping out of the shadow of N.W.A. and teaming with Public Enemy as he established his solo persona, Cube had become positioned as a unique voice for 1990s hip-hop; a rapper who could embody both the "gangsta" and the "topical" in a way that had initially seemed contradictory. And by years end, 2Pac would begin his rise to fame as an angry-but-charismatic young rapper who would master a similar balancing act and hold even greater sway.

But Chuck D was still a major force with a major platform--and Public Enemy had been holding court since 1988. On their fourth album, they showed no signs of slowing down--they simply streamlined their sound (slightly) and pushed forward. The group would convene at the Music Palace in Long Island, N.Y. to record Apocalypse 91...The Enemy Strikes Black, their first major statement of the 1990s (Fear of A Black Planet had been mostly recorded in 1989) and their last major statement before the rise of Death Row Records and G-Funk reshaped the hip-hop landscape drastically.

The album opens with the sonic assault of "Lost A Birth" and a declaration: "The future holds nothing else but confrontation." Over a barrage of samples that echo classic P.E., the track is mostly instrumental for almost a full two and 1/2 minutes until Chuck starts rhyming. It's a perfect opener and sets the tone for "Night Train," a song that centers Black faces that don't necessarily have Black interests at heart, those who are "trained to attack the Black, and it's true--'cuz some of them lookin' just like you."

N.W.A. had just released the brazen Niggaz4Life in May, an album that saw the now-quartet wallowing in the nihilism they'd fostered on Straight Outta Compton. Throughout their latest album, Dr. Dre, MC Ren, Eazy E and DJ Yella relished in murder and mayhem while celebrating the fact that they will be "niggas for life" and "real niggas don't die." On Apocalypse 91..., Flavor Flav offers a counterargument with the underrated "I Don't Wanna Be Yo Niga," an examination of the term as a sign of self hate masquerading as endearment. No one ever called P.E.'s infamous hypeman a major lyricist, but he always had a way with a hook and his cooky persona works well in the right settings.

"How To Kill A Radio Consultant" features Chuck taking aim at DJs refusing to play hardcore hip-hop, as he calls out anti-rap stations "ran by a sucker in a suit with slick black hair--and he don't even live here." It may seem like a dated argument (especially a subtle dig at A Tribe Called Quest in the last verse) considering how ubiquitous hip-hop is on mainstream radio in 2016, but most of Chuck's argument still holds true in an era of corporate interests determining most playlists.

Public Enemy had re-recorded their 1988 classic "Bring the Noise" with thrash metal stars Anthrax and released the collaboration that summer. The response had been strong from metal fans and the two acts would go on tour together. But the new "Bring the Noise" hadn't done much in rap circles, so P.E.'s new album would be more formally announced with a bombastic new single.

Released in early September, "Can't Truss It" announced that Public Enemy hadn't missed a beat in terms of focus or spirit. The album version opens with audio referencing the legacy of slavery in America and a snippet of Malcolm X declaring the recommendation of nonviolent protest "a crime" considering what Black people have faced in America. "Here come the drums!" announces Chuck as the anthem comes barreling out the gate; built on a backdrop of James Brown, Lafayette Afro Rock Band, Sly & the Family Stone, Im Nin' Alu and Slave's "Slide." The music video was one of the most effective and evocative of the 1990s; with Public Enemy paralleling slaves on 19th century plantation and Black factory workers of the early 1990s.

"'Can't Truss It' is about how the corporate world of today is just a different kind of slavery," Chuck would explain to Melody Maker shortly after the single's release. "We don't control what we create. And because of the media, we don't control the way we think or run our lives. We've got to limit working for a situation that's other than ours. We have no ownership of anything. If you don't own business, then you don't have jobs. White people have jobs because they have business. They have institutions that teach them how to live in America. Black people don't have institutions that teach them how to deal with s---. The Number One institution that teaches you how to deal is the family, but slavery f---ed that up. So the song is about the ongoing cost of the holocaust. There was a Jewish holocaust, but there's a Black holocaust that people still choose to ignore."

Corporate greed is an overarching theme throughout Apocalypse 91...The Enemy Strikes Black. "Shut 'Em Down" would become another of the group's most highly-touted singles, and it's a pointed look at how big money leeches off of Black communities without ever investing in those communities. "They don't want it to be another racial attack/In disguise so give some money back," Chuck raps. "I like Nike, but wait a minute/The neighborhood supports so put some money in it/Corporations owe/They gotta give up the dough..."

But the album's finest moment is the scathing "By the Time I Get to Arizona;" a vicious takedown of the state of Arizona and then-Gov. Evan Mecham who'd famously cancelled the Martin Luther King paid holiday in the state back in 1987-- and who'd told Black community activists that "You folks don't need another holiday. What you folks need are jobs." Mecham was later impeached following charges of the obstruction of justice and the misuse of government funds. Over an explosive sample of Mandrill's "Two Sisters of Mystery," Chuck rips into the governor and anyone who thinks King undeserving--while also issuing a warning: "Why I want a holiday?Fuck it--'cause I wanna--so what if I celebrate it standin' on a corner?/I ain't drinkin' no 40/I be thinkin' time wit' a nine/Until we get some land/Call me the trigger man..."

While the Bomb Squad oversaw the album, most of the production was courtesy of The Imperial Grand Ministers of Funk (Stuart Robertz, Cerwin "C-Dawg" Depper, Gary "G-Wiz" Rinaldo, and The JBL.) And Apocalypse '91... would be anchored by a slightly more groove-centric sound than P.E.'s previous two albums. Chuck and Flav's interplay is as strong as their respective perspectives; even though a takedown of the media ("A Letter to the New York Post") would be a bit more clear-eyed without Flav's defensiveness regarding his then-recent domestic abuse headlines.

Apocalypse 91... would be certified platinum within weeks of it's release in October 1991 and P.E. would open 1992 as still the biggest act in rap. But things were rapidly changing; N.W.A.'s breakup in late 1991 would set the stage for the 1992 rise of Dr. Dre and, by extension, Death Row Records and Snoop Doggy Dogg. As mainstream platforms rushed to embrace Dre's smoothed-out G-Funk via singles like "Nuthin' But a G Thing" and "Dre Day," and as other West Coast acts like Snoop, 2Pac and Ice Cube crossed over majorly throughout 1992 and 1993; P.E.'s sound and message suddenly weren't positioned at the forefront of mainstream hip-hop. By the time Public Enemy released it's follow-up, 1994s Muse Sick-n-Hour-Mess-Age, slicker sounds and gangster imagery had become standard and P.E. was pushed to the underground; becoming one of hip-hop's most enduring groups; but one that would eventually operate more as a legendary cult act, as opposed to chart-topping influencers.

Nonetheless, Apocalypse 91...The Enemy Strikes Black stands as the final chapter of the group's legend-making first period; a classic run of albums that began with 1987's Yo! Bum Rush the Show and that would influence the end of the 1980s and start of the 1990s in a way that could only be rivaled by N.W.A. Chuck D., Flavor Flav and Terminator X's first album of the 1990s was a timely look at how America saw Black people--and, aside from a few unfortunate moments of homophobia and subtle misogyny; most of it still rings true today. It says a lot about the art.

But even more about the society.

More From TheBoombox