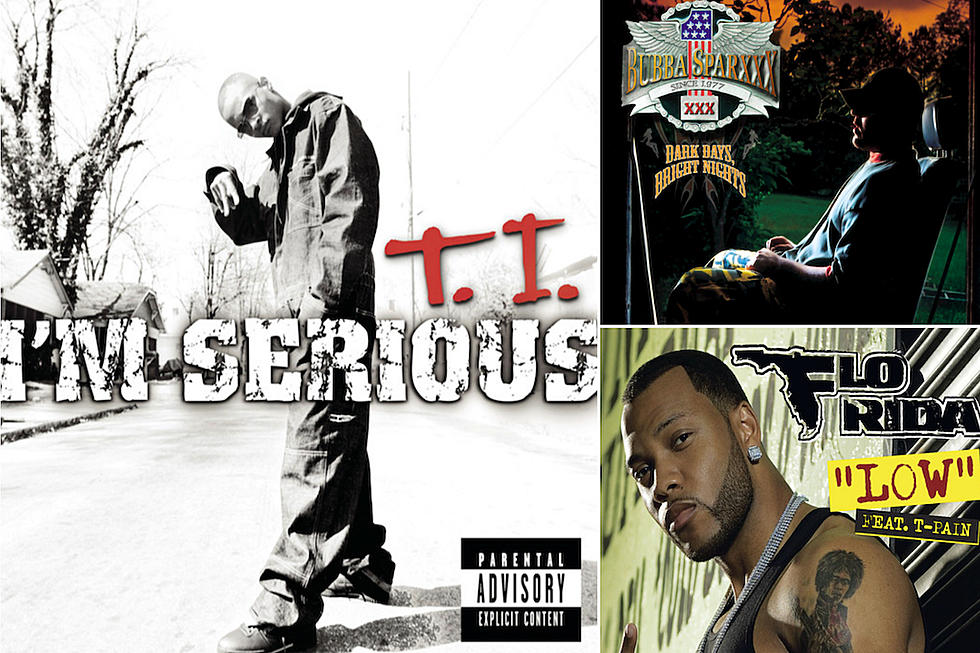

‘I’m Serious’ at 15: T.I.’s Overlooked Manifesto and the Rise of Atlanta Rap 2K

Why did the world ignore T.I.'s first album?

In 2016, the Bankhead-raised rapper is one of the most respected veterans in hip-hop. He's released 10 albums and sold 12 million records over the course of a often-stellar-but-sometimes-spotty recording career. He's also forged ahead as a mogul, spearheading Grand Hustle Films and partnering with 828 Entertainment to produce television projects--including his popular VH1 show, The Family Hustle. And he's experiencing something of a late-career renaissance; with the recent release of his acclaimed Us or Else EP.

But it didn't always look like it was going to happen for T.I.

At the dawn of the new millennium, Atlanta hip-hop was booming like never before. The Dirty South had gone from upstart "Third Coast" of the 1990s to ground zero for half of the hottest artists in hip-hop--and Atlanta, specifically, was now a thriving hub for multiplatinum rap artists, only rivaled by New York City. OutKast had dropped a smash album in 2000s Stankonia, a project that saw Andre 3000 and Big Boi become mainstream superstars after six years as critical darlings. Ludacris released his major label debut, Back For the First Time, a month later; an album that would spawn two Top 40 singles and sell more than 3 million copies. Lil Jon and the Eastside Boyz were also beginning to gain commercial steam after releasing Put Yo Hood Up in spring 2001, setting the stage for 2002s smash Kings of Crunk.

But Atlanta still hadn't produced the kind of singular figure that the streets could rally behind. OutKast had gone from teenage playas to Afrofuturistic innovators and Luda was great for a party but didn't really reflect the reality of street life. There was no one who occupied a space similar to what Jay Z meant to Brooklyn; or what Ice Cube meant to Compton. And that was why a brash young rapper from "the trap" seemed prime to be The Chosen One.

Young Clifford Harris had grown up in southwest Atlanta's famous Bankhead neighborhood, street hustling and spending summers in New York City with his father, Buddy Harris. His time in NYC was impactful; it exposed him to sounds that his fellow ATLiens were ignoring; and he was able to connect associates in New York to the sounds coming out of Atlanta at the time.

"[It] allowed me a certain diversity that contributed to my swag a little later on, you know what I'm saying?" Tip recalled in an interview with NPR back in 2014. "And it kinda put me ahead of people. Cause they wasn't — people didn't know – really, people didn't know about [A Tribe Called Quest] when I came back to Atlanta. Until like, you know, 'Bonita Applebum.' You know what I'm saying? People didn't really know about [the Notorious] B.I.G.! I came back and told people about B.I.G. It was the, I think, the year he was on the Craig Mack remix and he had things that were, you know, "Party and Bullshit," and other things that you would have to be in New York to have. And I went back to Atlanta with 'em like, 'Yo, this cat coming.'"

As Tip got older, he began to focus intently on his own career. He met Big Kuntry King when he was also an aspiring rapper, and the two began hustling their demo tapes together.

“Me and Tip were teenagers, always rapping and hanging in the streets, running around and being bad, basically” Kuntry recalled to VIBE in 2012. Kawan "K.P." Prather found Tip when he was a hungry rhymer, selling his tapes, and the A&R for LaFace connected immediately with the young emcee.

“We have a great chemistry based on being from the same place," Prather told Rolling Out in 2013. "Growing up in Atlanta and going through the obstacle course of the street stuff."

That obstacle course of street stuff formed the foundation for the burgeoning rapper's persona, as Tip's debut would be rooted in Bankhead swagger and identity; rubber bands, the trap and 24-inch rims providing touchstones for rhymes rooted in hood loyalty and Tip's own supreme confidence. Seeking a variety of sounds, Tip hit the studio with an enviable list of collaborators; from ATL mainstay DJ Toomp to Beenie Man, Jazze Pha and the Neptunes--who were white-hot hitmakers, having produced a litany of charting songs that were dominating the radio in 2000 and 2001.

Dope tales weren't new to hip-hop, by any means; but Tip's perspective, background and razor-sharp wit gave voice to a certain point-of-view on the drug trade and the culture that had grown up around it. Anthemic odes to the hustle ("Dope Boyz") sat alongside sober rumination on morality ("Still Ain't Forgave Myself") and Tip parlayed his own brand of smooth-talkin' swagger into club-friendly tracks like "What's Yo Name" and "Chooz U." It was clear that on his debut album the 20-year old was going after the streets and the charts--and he had the rhymes and the panache to become the kind of superstar rapper Atlanta was waiting for.

In the days prior to the release of I'm Serious, an unassuming Tip spoke to Down-South.com about the album and his ambitions were modest--but telling.

"You can just expect to ride to it, from the intro to the outro," he explained in regards to his forthcoming debut. "That's all I'm guaranteeing. It's something on there for everybody."

It all seemed primed for greatness. And Tip's confidence in his talent and approach was manifest in the moniker he'd brashly given himself: The King of the South. He'd announced himself as such on "2 Glock 9s" a track that had been recorded with Beanie Sigel for the Shaft soundtrack in 2000. Years later, T.I. admitted that his cockiness was the result of a dare--not necessarily a reflection of his own hubris.

At least--not at first.

"We were actually riding from Lenox, I think, one day. and we were listening to Mystikal, and Mystikal, I believe, said he was the Prince of the South," T.I. told BET in 2015. "I think that was his moniker. So I said 'How can there be a Prince of the South--who was the King of the South?' And KP said 'nobody--nobody ever said it.' I looked out the window and I looked at KP and he said 'I bet you won't do it. I bet you won't!' And I said 'why won't I?'

"I had no true conviction of it until after it hit and people started telling me what I couldn't say, what I couldn't be, how I couldn't--I'm like, 'hold up; last I checked, none of y'all muthafuckas was around when I ain't have shit. So you should have nothing to say.' I ain't scared of nobody. So it was that that kinda made me go so hard about it. And the fact that I just felt like it wasn't anybody in my generation at one album or two that could see me. I just knew it. I knew that they were solidified in the streets, but their artistry wouldn't carry them there--or their artistry was good but they wasn't solidified in the streets."

Tip was solidified, but dubbing himself King of the South was undeniably bold. And, as has been well-documented, there was the issue of Tip's name. He was signed to Arista, and so was Q-Tip, the well-established former frontman of A Tribe Called Quest who was coming off the success of hit singles like "Vivrant Thing" and "Breathe and Stop." The label wasn't about to risk confusing an established act with a rookie, so a decision had to be made.

"We were both on Arista and we was trying to release my first album," Tip told NPR. "The people who had to market, promote, and, you know, just spread the word on it communicated that it was somewhat difficult or confusing to have two Tips in one building. So out of respect and just the legendary reputation and career that preceded that situation, I definitely conceded. My problem, or conflict, at the time, was now this is what I've been called all my life, what do I change my name to?"

After a suggestion from KP, Tip became "T.I.," and I'm Serious was pressed with his new name. Armed with a Neptunes-produced lead single, a distinctive new name, all the ambition in the world and representing a city that was ready for a new voice; T.I. looked like a surefire superstar. But the "I'm Serious" single failed to crack the Billboard Hot 100 when it was released in the summer of 2001, and when the album dropped on October 9, 2001--I'm Serious was ignored by hip-hop fans outside of die-hards in T.I.'s home state. In a year that had seen Jay Z's The Blueprint drop a month earlier, Ja Rule's Pain is Love just a week before and with Luda's Word of Mouf and Nas' Stillmatic both soon-to-be released, I'm Serious barely registered.

Reviews were both pointed and praising of the Atlanta upstart's debut.

"Atlanta rookie T.I. wants to be taken seriously, but after listening to the first couple of tracks on his debut album, it's hard to do that," declared AllMusic. "The young rapper is filled with so much bluster and confidence that it's hard to take him at face value. I'm Serious is, after all, his first album, and he has the audacity to call himself the King of the South." HipHopDX wrote: "More country than red dirt, T.I. is one-third Scarface with the melancholy ('What Happened'), one-third Ludacris with the confidence (the title track, with Beenie Man) and one-third OutKast with his willingness to venture into new sounds (the heavy metal-esque 'You Ain’t Hard')."

I'm Serious would sell only 14,000 copies in it's first week. T.I.'s failed start would lead to Arista dropping him from their roster, and the rapper would soldier on as an independent artist--forming Grand Hustle Entertainment and dropping his P$C In da Streets mixtape series and Gangsta Grillz Meets In da Streets with DJ Drama. After appearing on fellow Atlantan Bone Crusher's hit single "Neva Scared," T.I. signed a joint venture deal with Atlantic Records in 2003 as he readied his sophomore album, Trap Muzik.

Of course, Trap Muzik would be released in August 2003 and would become T.I.'s breakthrough album; a platinum-selling classic that set Tip on the path to superstardom. In that same 2003 Whudat interview, on the heels of Trap Muzik's success, a vindicated Tip reflected on how his self-confidence remained unshakable even after the commercial failure of I'm Serious.

"Nobody would give me the support or the funds that I needed to do what I needed to do without some numbers first; without me proving myself," he said. "I don't have no problem with that, alright cool. I know what I can do. I knew that if I wasn't deserving then I wouldn't have even gotten this far. I wouldn't have even.. like, I came out with the first record and sold 14,000 the first week, and now with this one I'm doing 250,000 strong. I don't know anybody else who sold 14,000 the first time out and ended up with 250,000 two years later."

T.I.'s debut may not have set the world on fire at the time, but much like Jay Z's Reasonable Doubt, it would prove to be both a snapshot of everything that made the rapper so vital in his early years and an important touchstone for those who would follow in it's wake. There is much debate as to where "trap music" really began--and one could make a case for artists as far back as UGK or as recent as Gucci Mane; but it's hard to ignore the role that I'm Serious played in streamlining the image of the trap and the rappers who would come from it. From Young Jeezy to Waka Flocka Flame to Rick Ross, it's easy to see how the influence of that album and T.I.'s image stretched far and wide across southern hip-hop in the 2000s. There was less emphasis on the earthy sounds of the Dungeon Family or the southern-fried soul of Suave House; and more on digitized-but-dirty beats and dope boy tales that reflected the nervy energy of a new generation. And in representing a singular point-of-view as opposed to a collective, I'm Serious set T.I. apart from acts like the ones that had emerged out of New Orleans-based labels like No Limit and Cash Money Records.

T.I. seemed to foresee all of it. Even if it took the world a while to catch on. So why did the world ignore T.I.'s first album? Maybe I'm Serious was just ahead of it's time--by a year or two.

"If I wasn't that strong, if I wasn't really happening like I say I am, then I wouldn't be here still," Tip said in 2003. "I just knew the next thing I released would be even bigger and better, because I knew I could do better. So it was just about me putting the music out there, keeping the streets familiar with who I was and going to other regions, utilizing my resources and making it happen.

"Eventually everybody else started to see it. From Puff to Atlantic to Def Jam--all the rappers respect me."

Long live the King.

More From TheBoombox